Taxonomies

LEGAL MÉTISSAGE IN A MICRO-JURISDICTION:

THE MIXING OF COMMON LAW AND CIVIL LAW IN SEYCHELLES

MATHILDA TWOMEY (née BUTLER-PAYETTE)

BA (Eng/Fr Law), Dip (Droit Francais), Barrister-at-law (Middle Temple), LLM (Public Law)

NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND,

GALWAY

This Thesis is submitted to the National University of Ireland Galway for the Degree of PhD in the School of Law.

Head of School: Professor Donncha O’Connell

Supervisors: Ms. Marie McGonagle, National University of Ireland, Galway

Dr. Seán Patrick Donlan, University of Limerick

July 2015.

For Aoibhín, my precious little light.

|

CE QUE TU ES

Un mélange de sang Accouplé d’une mêlée végétale.... Race ou peuple ou nation? Prends qui tu veux; Tourne-lui sa peau, Et tu verras Un brouillamini Un casier Un cosmos. Les huttes, Les cases, Les toits coloniaux, Le parler, Le langage La langue L’expression La chaleur phonétique Un univers unique et varié Un métissage de sons et de couleurs Un arc-en-ciel dans un ciel. Bourré de soleils, Et les temperatures qui alternent charnellement Physiquement, psychiquement....... Une brassée, Une envergure, Une coudée De négritude perdue et retrouvée

Antoine Abel

|

WHAT YOU ARE

A blend of blood

Bonded with a tussle of vegetation … Race or people or nation?

Take whoever you will; Unfold his skin, And you shall see An imbroglio A maze Outer space. The huts, The houses, The colonial-styled roofs,

The vernacular, The language The tongue The expression The phonetic warmth

A world apart and multi-faceted A métissage of sounds and colours A rainbow in the sky.

Full of many suns, And temperatures which alternate carnally

Physically, psychically…

An armful, A wingspan, A leeway Of negritude lost and regained

Antoine Abel (Translated by Alain Butler-Payette) |

SA KI OU ETE

En melanz disan

Bennyen dan en touf verdir... Ras, pep ou nasyon?

Pran sa ki oule Devir son lapo E ou ava vwar En melimelo En kazye Lespas. Bann kabann, Bann lakaz Bann twatir stil kolonyal, Fason koze, Langaz Lalang Lekspresyon Lasaler fonetik

En monn inik dan son diversite En metisaz son ek kouler En larkansyel dan lesyel. Ranpli avek soley E tanperatir ki sanze sansyelman

Fizikman, mantalman...

En bras, En lanvergir, En marz liberte Negritid sove e retrouve

Antoine Abel (Translated by Alain Butler-Payette) |

Table of Contents

1.1 The Scope of the Research 14

1.5 The Organisation of the Thesis 19

Chapter 2 Conceptualisations of Law 24

2.1 The Complexity of Official Law 27

2.1.1 Roscoe Pound: The Law-in-Books and the Law-in-Action 27

2.1.3 Rodolfo Sacco and Legal Formants 31

2.2 The Significance of Unofficial Law 33

2.2.1 Eugen Ehrlich and the Living Law 34

2.2.2 The Varieties of Legal or Normative Pluralism 35

2.2.2.1 Classical Legal Pluralism 37

2.2.2.2 New Legal Pluralism 38

2.2.2.3 Global Legal Pluralism 39

2.2.2.4 Critical Legal Pluralism 40

2.3 Additional Cultural, Political and Economic Influences 41

2.3.1 The Experiences of Micro-Jurisdictions 43

2.3.2 Language and Anglo-American Hegemony 45

2.3.3 Post-Colonial Thought and Hybridity 46

Chapter 3: The Evolution and Transferability of Law 49

3.1 Comparative Law, Taxonomy and Legal Traditions 49

3.1.2.2 Methods of Classification 59

3.1.2.2 (a) Systems and Families 60

3.1.3. Major Legal Traditions 66

3.1.3.1 The Civil law Tradition 66

3.1.3.1 (b) Legal Structures 69

3.1.3.1 (d) Sources of Law. 71

3.1.3.1 (e) Substantive and Procedural Law. 73

3.1.3.2 The Common Law Tradition 74

3.1.3.2 (b) Legal Structures 78

3.1.3.2 (e) Procedural and Substantive Law. 83

3.1.4 The Movement of Legal Traditions and Legal Receptions 86

3.1.4.1 Alan Watson and Legal Transplants 87

3.1.4.2 William Twining and Diffusion 89

3.2.2 Classical Mixed Jurisdictions 92

3.2.3 The Third Legal Family 93

3.2.4 The Expansion of the Debate 94

Chapter 4 - The Creation of the Seychellois Legal Tradition 98

4.1.1 Discovery and Settlement 99

4.1.3 British Rule and the Inter Colonial Transfer 105

4.1.3.1 The Effects of Capitulation 105

4.1.3.2 The Initial Mixing of Common Law and Civil Law 107

4.1.3.3 Vigorous Mixing in the Twentieth Century 110

4.1.4.2 Ramifications of the End of Colonialism 114

4.1.5 Three Republics and Three Constitutions 116

4.1.5.1 The 1st Republic 1976-1977 117

4.1.5.2 The 2nd Republic 1979-1993 118

4.1.5.3 The 3rd Republic of Seychelles 1993- 120

4.2.1 Legal Training and the Legal Profession 121

4.2.1.2 The Legal Profession 124

4.2.2 Political and Legal Structures 127

4.2.2.3 The Judiciary and the Courts 131

Chapter 5 – Substantive and Procedural Law of Seychelles 149

5.2.1.1(b) The Distribution of Property on Termination of Marriage and En-Ménage Relationships 155

5.2.1.2 (a) Intestate Succession 160

5.2.1.2 (b) Succession by Will 161

5.2.1.3 (a) The Fiduciary and the Co-ownership of Property 162

5.2.1.3 (b) Conveyancing and Registration 165

5.2.1.3 (c) Rights In Rem and Rights In Personam 166

5.2.1.3 (e) The Droit de Superficie 172

5.2.1.4 Law of Obligations 174

5.2.1.4 (a)(i) The Validity of Contracts and Nullity. 175

5.2.1.4 (a)(iii) Frustration of Contracts 180

5.2.1.4 (a) (iv) Object, Cause and Consideration 181

5.2.1.4 (b)(i) Fault and Strict Liability 191

5.2.1.4(b)(iii) Defective Goods 194

5.2.1.4 (c) Unjust Enrichment 199

5.2.1.5 Corporate and Commercial Law 200

5.2.1.5 (a) The Companies Ordinance 1972 201

5.2.1.5 (b) International Business Companies 202

5.2.1.5 (c) The Commercial Code of Seychelles 203

5.2.2 Public and Criminal Law 206

5.2.2.1(a) Constitutional Law 207

5.2.2.1(a)(i) Constitutional Principles 208

5.2.2.1(a)(ii) The Charter and its Interpretation 209

5.2.2.1(a)(iii) The Spectrum of Rights 211

5.2.2.1(a)(iv) Constitutional Adjudication 215

5.2.2.1(b) Administrative Law 217

5.2.2.1(b) (i)The Nature of Judicial Review 218

5.2.2.1(b)(ii) Principles of Judicial Review 221

5.2.2.1(c)(i) The Penal Code and its Interpretation. 223

5.2.2.1(c)(iii) Money Laundering 228

5.2.2.1(d) The Misuse of Drugs 230

5.3.1.2 Petitory and Possessory Actions 234

5.3.2.1 Powers of Arrest, Bail and Remand 236

5.3.3.1 Oral Evidence in Civil Cases 243

Chapter 6: The Seychellois Legal Tradition 247

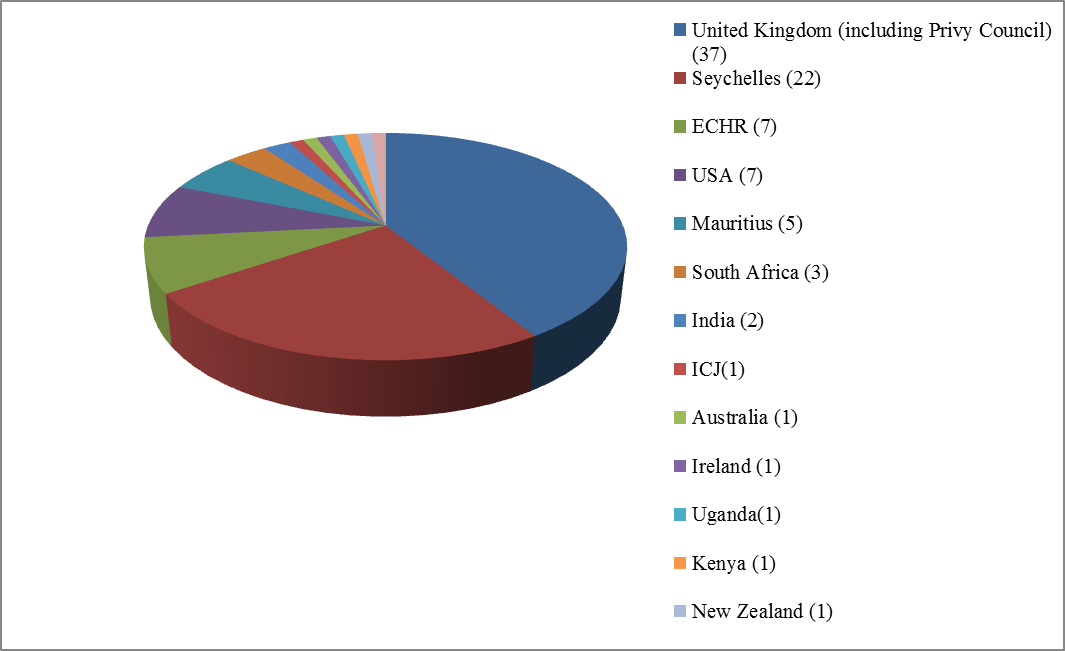

6.2.1 Data and Methodology 249

6.2.3 (a) Mixing within the Constitutional Law of Seychelles 251

6.2.3 (b) Mixing within the Criminal Law 254

6.2.3 (c) Mixing within the Civil Law 256

6.2.3 (d) Mixing within Legislation generally 258

6.2.4 (a) Adjudication and the Weight of Jurisprudence 260

6.3. Unofficial Law in Seychelles 267

6.4 Additional Cultural, Political and Economic Influences 274

6.4.2 Post-Colonial Thought, Language and Legal Hybridity. 277

6.4.3 Regional and International Influences 281

6.4.4 The Role of Foreign Judges in Seychelles 285

Chapter 7: Final Analysis and Conclusions 289

7.3 Research Results and Analysis 290

7.3.2 The Movement of Legal Traditions 291

7.3.3 The Formation of the Seychellois Legal Tradition 293

7.3.4 The Future and Sustainability of the Seychellois Legal Tradition 295

Southern African Development Community Tribunal 351

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge and especially thank my two supervisors, Ms. Marie McGonagle and Dr. Seán Patrick Donlan for a memorable three years. Much coffee was consumed and so much support and encouragement was given. I have been overwhelmed by your generosity and have gained two exceptional friends and I am deeply honoured and privileged to have been able to work with you both.

I would also like to thank the members of my Graduate Research Committee, Professor Donncha O’Connell, Thomas O’Malley and Dr. Eoin Daly for their kind support.

A number of other people have helped me on this journey: I would like to remember Judge André Sauzier who nurtured my legal education from a very young age, who read my early drafts on Seychellois law and encouraged me with love and understanding. He has since passed away but lives on in my heart and in the courts of Seychelles.

My brother, Alain Butler-Payette in Seychelles, for his unstinting support especially this past year and for his painstaking translations, especially of Antoine Abel’s poem. Caoilte and Petra Breatnach for their meticulous proof reading, Sunday morning coffees, and care for my sanity.

My colleagues Dr. Connie Healy and Dr. Charles O’Mahony who particularly helped me through the rough patches and others who nudged me on when my energies and spirit flagged – Dr. Ciara Hackett, Dr. Anne Egan, Ursula Ni Chonghaile, Nicola Murphy, Lughaidh Kerin and Deirdre O’Halloran.

The Adminstrative Staff of the Law School especially Carmel Flynn and Tara Elwood for their patient help at all times.

Professor Anthony Angelo and Judge Bernard Georges for our long chats in Seychelles and via email.

My students, especially the LLB tort class of 2014, for the entertaining chats and cup cakes.

My good friends in Kinvara who put up with me – Inigo Batterham, Rosaleen Tanham, Pam Fleming, Hazel Walker, Cath Taylor, Trish Thompson, Helen Murphy and Roger Phillimore.

My other brothers and friends in Seychelles: Flavien and Gilles Butler-Payette, Sue Ansell, Russell Thomson and May de Silva, for their generosity and love.

A special thank you to my four wonderful children Seán, Dominique, Camille and Aoibhín for their kind words, patience, love and hugs without which I could not have completed this thesis.

I would also like to thank the Hardiman Research Scholarship Board and the Irish Research Council for funding my research.

Abstract

This thesis is an exploration of the laws of Seychelles in terms of their genesis, evolution and status today. While all legal traditions are hybrids, so-called mixed legal systems where laws are explicitly the product of different traditions, provide a unique perspective on the process of the movements and mixing of laws. In the Seychellois national language, kreol, a metis is someone of mixed parentage. This métissage of race, culture and language is parallelled in its legal system.

These small islands, in the middle of the Indian Ocean, colonised twice, combine French and English legal ideas in a non-Western setting. Recently, the world recession has brought new challenges in the form of a third wave of quasi colonisation with the bail out of struggling economies, including Seychelles, by financial bodies like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund which, as part of the aid packages, impose homogenous common law style legislation.

The research is a comparative analysis of the Seychellois legal tradition. Seychelles is also, given its small size, one of many micro-jurisdictions around the world. As with mixed systems, such small legal orders provide important information for general legal theory.

The thesis adds to the understanding of both mixed and micro-jurisdictions, and as a result, allows a reconsideration of the relevance of both to comparative law. It permits an examination of the utility of contemporary legal taxonomies, rooted in Western experiences, to non-European, post-colonial jurisdictions. The Seychellois experience may have important lessons for legal transplantation, reception and harmonisation of laws as well as relevance for colonialism (including neo colonialism) and culture and for the viability and sustainability of such mixed systems of law.

Chapter 1 - The Past, the Present and the Future of the Seychellois Legal Tradition Within the Context of Other Legal Traditions.

“[The salmon is] an intriguing and ambiguous fish, at home in both fresh and salt water. It migrates thousands of miles to regenerate itself; it swims against the current rather than with it… And, after doing all this, it still has the energy and cunning to spawn something personal and new.”1

1. Introduction

Gavin Jantjes, an artist who works both in Africa and Europe, compares himself to a cultural salmon. A native of Cape Town, South Africa, he studied at the University of Cape Town’s Michaelis School of Fine Art and the Hochschule für bildende Künste, Hamburg, Germany where he received a master’s degree in 1972. Jantjes was designated by the apartheid regime as Cape Coloured. He felt that he had to become a determined all-rounder to pursue “the modernist thesis of questioning the world and the art produced in it.”2 On reaching Europe however, he found that modernism was not the international, universalist movement it claimed to be. It did not initially welcome his kind of questions.3 Modernism attempted to reduce him to merely an African artist who could not make statements about art which might be of global interest.4 Jantjes continued to challenge this view emphasizing that one has to keep an open mind and “has to be aware that the world, as known, could be and will be re-formed, re-thought and redescribed…”5 As a cultural salmon, he sought recognition of an in-between or liminal status or identity, at once rooted in place, but more than that place.

In parallel, African legal systems may be viewed as legal salmon which can swim against the current, adapt, remodel, and regenerate while also remembering6 and imagining. Many African nations share a broadly common history of colonisation by European powers.7 But before this occurred, African regimes, communities and tribes had their own norms, mores, traditions, customs and indigenous laws or customs.8 The fusion of these indigenous traditions with the imposed normative and legal traditions of Europe has spawned legal systems that have been labelled exotic, mixed,9 pluralist10 or hybrid.11 Internally, however, there is considerable legal instability within those systems. In practice, African nations have to navigate complex crosscurrents of indigenous and customary laws12 and inherited and infused13 European colonial laws.

These African legal systems are attracting ever-greater attention from jurists. Most legal scholarship, however, seems to be written from the perspective of European or Western authors. In this writing, it is hard to hear the voice of the African comparative legal scholar.14 In the twenty-first century, as decolonisation is nearly complete, African states have questioned and challenged their identities, as well as the West’s view of them as the Other.15 In this respect Edward Said’s orientalism is equally applicable to Africa and it is just as incumbent on them, as other non-Western nations, to ignore the oversimplified view of their cultures as formulated by the West and to challenge the West’s view of them as being extremely different and inferior, marginalised but also in need of intervention or rescue.

As a result, it is necessary that African jurists evaluate and articulate their social and legal traditions. They may even be seen to have a special role to play in comparative law. Given Africa’s experience of native customs, the positive laws of Europe and the reconfigured laws after colonialism, its scholars can generally inform other jurists, free western legal scholars from cognitive lock-in16 (where one limits oneself to appreciating another entity purely in terms of the measure of oneself) while contributing to the emerging, meaningful global perspective on laws. It is by showing difference to others, that identifying one’s identity is possible.17

Seychelles has had a somewhat different legal experience from most its African neighbours. An archipelago far from the African mainland, it is geopolitically part of Africa. But it has no indigenous peoples. Its population was created through the encounter between white colonizers and African slaves. That experience must be explored, however, within the context of its complex colonial past. While clear-cut divisions existed historically between plantation owners and their slaves, time has assimilated the population into a Creole18 people. There are no distinct races in Seychelles today: it is a state with an explicitly hybrid nation.19

This hybridity is parallelled in its legal system, caught in the conflicted identity of the law of the coloniser and the colonised. That legal tradition is complicated by the heritage of double colonisation by first France, then Britain. The result is a micro-jurisdiction that combines both the civil law of France and the common law of England. Caught between European, colonial legal traditions and the legacy of its African heritage, the Seychellois legal tradition is now seeking its own identity. This is complicated not only by its past, but by new global forces. The place of Seychelles at the nexus of this complex independence and interdependence between legal traditions is explored in this research,20 including the question of the future sustainability and autonomy of its own legal system given powerful outside influences.

1.1 The Scope of the Research

Every legal system is the product of complex traditions: civil law, common law, Islamic law among others. Many studies have been carried out on systems that explicitly combine one or more of these traditions: for example, Scotland, Quebec, Louisiana and South Africa. Indeed, it is increasingly accepted that all legal systems are both mixed and mixing. For example, European law and the laws of different member states are mixed into the laws of other member states. What are less well-understood are the consequences of such mixing. This study aims specifically to research the explicit hybridity of Seychellois law and its relevance as a micro-jurisdiction and to track its legal evolution. The objective is then to draw lessons, if any for other current mixes or for nominally uni-jural systems.

No previous substantial research has been carried out on the Seychellois mixed jurisdiction. This thesis articulates and theorizes the Seychellois legal tradition in a way that is practical and useful both to Seychellois and to the rest of the legal community, especially to comparative legal scholars. Seychelles is a micro-jurisdiction with apparently little or no influence on the rest of the legal world. But its experiences provide a useful, manageable laboratory for understanding the ramifications of changing legal traditions in an increasingly interlinked global context in which exterior forces have ever-greater effects on national laws.

The Seychellois legal tradition has changed and continues to evolve, as all legal traditions do. By looking at the past and the future in relation to those historic changes and the surrounding contemporary power dynamics and influences, this research explores these different connections. The potential contributions from the new global community are now leading to a developing if not enduring legal tradition though not in the shape or form in which it might have originally been conceived.

This research situates the Seychellois legal tradition within the language of legal families. Its theoretical approach acknowledges the difficulty in conceptualising law both generally and in the context of other concepts such as legal traditions and legal culture. It also recognises the limitations of legal taxonomy, the peculiarities and complexities of the associated vocabulary and linguistics of legal pluralism, and the numerous theories about the movement of legal traditions and receptions.

Academic literature on mixed jurisdictions, hybridity and pluralism is vast and continuously expanding. The theories surrounding these concepts are fluid and constantly evolving and it is sometimes difficult to keep up with such changes.21 It is acknowledged that there is more than one possible definition or understanding of these concepts. For a comprehensible and efficient study of the Seychellois legal tradition, this research employs the traditional taxonomy of legal families (in particular, the common division of civil law and common law), together with the concepts of mixed jurisdictions and the third legal family.22

Further, the examination of the substantive and procedural laws of Seychelles will be limited to the extent that the whole law of Seychelles cannot be explored in depth in this thesis. Only some important aspects are examined in detail and a tentative exploration of the future of the tradition reconnoitred.

1.2 Research Questions

This thesis assesses the reasons for the mixing of laws in Seychelles and examines whether the incorporation of laws from two diverse legal traditions and their subsequent assimilation within the context of Seychelles has resulted in a distinctive and coherent set of laws. It analyses, in light of the growing scholarship on mixed legal systems, the past and present role of civil law and common law within the Seychellois system. It explores the inherent tension, the sustainability of the law, and queries whether Seychellois bi-juralism - if that is what it is - works as well as nominally uni-jural systems. It evaluates the adjudication mechanisms and jurisprudence of the system, in particular in specific areas of public and private law.

My research inquiry is therefore composed of the following questions:

-

What is the law and legal system of Seychelles?

-

How does adjudication take place in Seychelles?

-

Is the legal tradition of Seychelles distinctive? If so, what is its taxonomical status?

-

Is the Seychellois legal tradition sustainable, given both its status as a mixed jurisdiction and a micro-jurisdiction?

-

Is the Seychellois legal tradition relevant for other jurisdictions where the mixing of laws is ongoing? If so, what lessons if any can be learnt from the Seychellois experience?

-

Does Seychellois law offer anything new to the understanding of mixed and micro-jurisdictions?

-

What is the significance of Seychellois law to comparative law?

1.3 Rationale

Over a decade ago, George Gretton noted, in writing about Scots property law that “one can live and work in a system and still massively fail to understand it in context.”23 Such peripheral blindness is common across a number of legal traditions and systems. And so it was in relation to my own personal experience of working as a legal practitioner in Seychelles. I oriented myself across the complex mixity of its laws without once stopping to query its peculiarity. It was only in the recent past during the course of academic research in Europe, far away from my native shores, that I gained a new perspective into Seychellois law.

There appear to be very few legal systems like that of Seychelles in the world. Vernon Palmer identifies only sixteen such mixed jurisdictions worldwide, systems “where common law and civil law co-mingle and constitute the basic materials of the legal order.”24 But the small mixed system of Seychelles is virtually unknown to western lawyers.

This research marks the beginning of a comparative investigation into Seychellois law and its legal institutions in the hope of bringing them into greater focus and understanding. It is a contribution not only to the ever expanding bounds of comparative law, but also as an outreach by this micro-jurisdiction to the outside world.

1.4. Methodology

No single methodology is adopted in this thesis. Generally, the study uses the comparative method of legal research which questions the role, function and value of legal traditions. Recognising the complexity of the analysis of a legal tradition, other methods are used for distinct elements of the study where they are judged best suited to the particular objectives of the different components of the research.

In terms of the theoretical framework of the thesis, an inquiry into the conceptual bases of the legal rules, principles and doctrines of the Seychellois legal tradition is made. It is undertaken through the lens of the comparative legal method, enquiring into the similarities and differences between major legal systems and that of Seychelles. Comparativists generally contend that this approach is the best tool for a deep understanding of legal systems.25 It is utilised particularly to study legislative texts, jurisprudence and legal doctrines, especially of laws from other civil law and common law traditions. In this context, it allows a unique understanding of how the law works within Seychellois culture.26

In terms of the substantive and procedural laws of Seychelles, the doctrinal approach is used to provide a systematic exposition of the rules governing the legal categories concerned and to analyse relationships between legal rules. It also helps to explain areas of difficulty and in predicting the future development of the legal tradition.27 Doctrinal research is also used to locate the law of Seychelles. Its case law and statutory law are examined for their consistency and certainty. The purpose and policy of some of the existing laws and legal institutions is scrutinised.

A qualitative analysis is used for identifying existing primary sources of information. The existing literature on comparative law and mixed jurisdictions was reviewed by accessing European, African and international electronic databases. Raw materials were accessed through the Hardiman Library in the National University of Ireland, Galway, the Glucksman Library in Limerick, the Seychelles Supreme Court Library and other libraries. A scrutiny of the colonial records in the Seychelles and Mauritian National Archives and Colonial Office papers housed at Kew, London and the Archives Nationales de Paris was also undertaken. Similarly, the papers of General de Caen at the Bibliothèque de Caen, France were examined and critically reviewed to explore the genesis of Seychellois law, and to lay the foundations for the research for the thesis.

Where the doctrinal method was not useful, the socio-legal method was used. This was particularly so in the case of identifying approaches in the practical application of the law in Seychelles. In general, the socio-legal method is useful to research the origins, operations and effects of legal traditions and the policies and practices necessary to understand law as a social phenomenon. In this sense it is used to look into the social dimension of Seychellois law and to identify the gaps, if any, between the law-in-books and law-in-action.28 In addition, the systematic observation of law-in-action in Seychelles was undertaken through participation by the researcher in the Court of Appeal of Seychelles and in the work of the Law Revision Committee on the Civil Code of Seychelles.

Empirical legal research is carried out into two distinct aspects of Seychellois law: firstly, the mixing of laws within the constitutional, civil and criminal law contexts and secondly in the process of adjudication to analyse the weight of jurisprudence. This provides an insight into the trajectory of the developing Seychellois legal tradition. It delivers a basis for forecasting the nature of the tradition from the perspective of the mixing taking place.

This thesis explores Seychellois law with the backdrop of legal philosophy to evaluate the status and development of its laws. Micro and macro comparisons are used to assess the sustainability and legitimacy of the Seychellois legal system and assess its relevance to European and other jurisdictions where the mixing of law is ongoing.

1.5 The Organisation of the Thesis

This thesis is composed of seven chapters. Chapter 1 lays the foundation for assessing the Seychellois legal tradition. The introduction puts Seychellois law within African and European law and ongoing legal developments. In this way, the legal tradition is located within the most commonly-used legal taxonomies. The fact that the Seychellois tradition, like other legal traditions, is a dynamic process and subject to change is explored briefly. Some of the limitations of undertaking research in such an area with little previous academic interest are also examined. The methodology employed is discussed with some explanation for the choice of the methods used in the study.

Before the legal tradition of Seychelles can be explored, it was necessary to define law, at least for the purposes of this study. Chapter 2 explores the meaning of law and describes some conceptualisations of law by both comparatists and jurisprudes. It begins by distinguishing law and norm and the related concepts of official law (state or institutional law) and unofficial law (usually non-state normativities).29 The contribution of Roscoe Pound30 in identifying and articulating the gap between the law-in-books (statutes, regulations and law reports) and law-in-action (law as practised and experienced in the social arena) is explained. Recognition of the wider context of law outside the state, law that is other law- like normativities are then examined.

However, the difficulty of identifying a suitable vocabulary to describe non-state law is particularly challenging; there seems to be no inclusive terminology for different types of normativities outside the western concept of law. Rodolfo Sacco’s formants of legal systems31 and Eugen Ehrlich’s idea of living law32 challenging the centralism of official law are looked at. Different varieties of normative pluralism, including the definitions and expositions of William Twining, Jacques Vanderlinden, John Griffiths and Brian Tamanaha are compared together with a short exposé of classical legal pluralism, new legal pluralism, global legal pluralism and critical legal pluralism. Chapter 2 also surveys cultural, political and economic influences on law. Finally, the special status of micro-jurisdictions, language and post-colonial theory are briefly examined for their influence on the constitution of law.

Chapter 3 seeks to locate the Seychellois legal tradition within traditional or common legal taxonomies. However, before this enterprise can be undertaken, the use of the comparative approach to the study of jurisdictions is explored. This approach is broken down into the descriptive positivist, the functional and the contextual methods. These methods are briefly explored, after which the contextual comparative law methodology for this research is adopted. Chapter 3 then looks at the purposes of taxonomy generally together with the main methods of classification. This includes the better-known taxonomies of René David and John Brierly33 and the expanded classification of Konrad Zweigert and Hein Kötz.34 The distinction between the nomenclature of legal system and legal tradition is then addressed with a discussion of the approach taken by Patrick Glenn.35 His definition of legal tradition, which conveys a continuous process of legal development, is radical. However, his reduction of these traditions into only seven classes (the chthonic, talmudic, civil, Islamic, common law, Hindu and Confucian traditions) is too limited. It does not for example provide an appropriate appreciation of the diverse African normativities. The approach of John Bell36 in using the concept of legal culture as a method of classification is also addressed as is the novel approach by Ugo Mattei in moving away from both geographic and cultural taxonomies in his concept of patterns of law.37 Chapter 3 also examines Boaventura de Sousa Santos’ metaphors of law38 and Esin Örücü’s family trees39 approach to situating and understanding those legal traditions taking new shapes and forms.

Against this backdrop of taxonomies and groupings, a more focussed study is then carried out on two major legal traditions that were to be incorporated into the Seychellois legal tradition, namely the continental European legal tradition (civil law systems) and the Anglo-American legal tradition (common law systems). Chapter 3 also addresses the concepts of legal movement and reception, namely Alan Watson’s theory40 of legal transplants and William Twining’s concept of legal diffusion.41 These concepts are important tools in understanding the formation of the Seychellois legal tradition, as is the discussion on mixed legal systems and mixed jurisdictions and their definitions. The classificatory limbo42 and the distinguishing characteristics of such systems conclude Chapter 3.

With the definition and classification of legal systems and traditions established, Chapter 4 relates in some detail the genesis of the Seychellois legal tradition. Its historical foundation with the first settlement by the French in the early eighteenth century together with its links to Mauritius as a colony within a colony is narrated. French rule and the early imposed laws are examined. The application of different laws to different classes of people depending on race and status (the white settlers, the black slave and the coloured and freed slaves) is explained. A summary of the early laws is detailed, from the laws of the Compagnie des Indes to the royal decrees and the edicts published by the Colonial Assembly of Mauritius and the laws of Decaen. The Indian Ocean Wars between Britain and France which were part of the global wars of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the eventual capitulation of Seychelles to Britain in 1810 are described. British rule and the first laws, the Code Farquhar and the gradual superimposition of some British law onto the French laws of the colony are discussed. This initial mixing of laws was followed by a more pronounced form of legal transplantation both in the substantive and procedural law of Seychelles. The more pronounced common law traits in the law in the years after 1903, when Seychelles was detached from Mauritius and became a fully-fledged colony in its own right, is also considered. The journey of Seychelles to independence, recodification and a series of three constitutions as a republic is then examined. The present legal system and structures are also explored.

Chapter 5 is an in-depth study into the substantive and procedural law of Seychelles today. Aspects of the private law, namely elements of family law including descent and the distribution of property on termination of marriage and en-ménage relationships, are examined. This is followed by a study of the laws of succession and property law. Chapter 5 also includes a treatise on the Seychellois law of obligations comprising of contracts, delicts and unjust enrichment. Next, some elements of the corporate and commercial law are pointed out. The chapter then moves on to the examination of public law with an exposé of the constitutional and administrative law of Seychelles and the current development of democratic principles through the vindication of constitutional rights of citizens before the Constitutional Court and the Court of Appeal. The criminal law of Seychelles is scrutinised, with a description of some of the new measures introduced to combat modern day crime including anti-money laundering and marine piracy together with the rich case law it has already generated. Lastly, its mixed procedural laws, including the law of evidence and civil and criminal procedural rules are analysed. The chapter contains a discussion of the laws in the specific areas mentioned with some comparison to both English common law rules and French civil law rules when these have had or continue to have a bearing on the extant and developing laws of Seychelles.

Chapter 6 begins with a bird’s-eye view of the Seychellois legal tradition, followed by a more detailed analysis of some particular aspects of the law. The mixing process uncovered through the preceding chapters is examined in more depth to understand the trajectory of the development of the Seychellois legal tradition. The complexity of both the laws and the domestic, regional and international forces at play are identified and viewed on the one hand through the lens of the official law, and then on the other hand through that of unofficial law. This is facilitated through two pieces of empirical research into the official law. The first element of research involves a study of citation patterns in the case law of Seychelles in constitutional, criminal and civil actions. The second piece of research examines the adjudication process in Seychelles in terms of the nature of the bindingness of precedent. Some reasons for confusion in the application of precedent are suggested and the findings and suggestions of the Committee reviewing the Civil Code of Seychelles are included. As a contrast to official law, the unofficial law of Seychelles reveals elements of African culture that have endured despite state legislation. Unofficial law has also become part of the fabric of the Seychellois legal tradition. Chapter 6 ends with a consideration of the modern influences on Seychellois law including cultural, political and economic forces. The part played by post-colonial thought, including the concept of creolité, (the interactional or transactional aggregate of European and African elements united on the same soil by the yoke of history)43 is considered. Regional and internal influences, including the membership of Seychelles in the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA)and the Southern African Development Community (SADC), and the role of foreign judges are also examined. Finally, the enduring legacies of socialism and one-party rule and the influences of globalisation are studied.

Chapter 7 concludes the thesis. It briefly summarises and restates this thesis’ findings about the complexity of the laws of the micro-jurisdiction of Seychelles. It opines on its living legal tradition and comments about its future. It does so based on the results of the research findings and an analysis of the global forces at play. It reflects on the research findings in light of the theoretical framework to explore the place of the Seychellois legal tradition within the wider context of the family of legal traditions and legal systems. It considers the legal and social changes that reflect the complexities of current politics and offers some lessons that may be learned from the mixing of laws in Seychelles. Finally, it proposes some areas that might benefit from further research and bring more clarity in the area of mixed jurisdictions.

1.6 Chapter Conclusion

My greatest hope in articulating the Seychellois legal tradition is that it provides a better knowledge of the laws of this small jurisdiction. I recognise that there will be ongoing questions about aspects of its legal system but it is my belief that a lot is to be gained if at the very least it engages the wider community in discussions around creative and critical ways of thinking about mixed jurisdictions. The formation of such systems, either by design or accident, is fascinating in itself. Even more so, their development when viewed from an international perspective may result in some positive interlegality,44 that is, where choices are made by a jurisdiction in adopting rules and norms of another jurisdiction where it deems it favourable to do so.

I have been guided in this research by certain factors: firstly, that the Seychellois micro-jurisdiction is important and needs to be appreciated and recognised as such even if only by the local practitioners and academics. Secondly, I have framed the Seychellois legal tradition in the context of some conventional theories about law. Thirdly, knowledge of the tiniest jurisdiction founded on two legal traditions, civil law and common law but interspersed with some indigenous law may bring rich comparisons and further understanding of law in general. Finally, the research sets out to bring greater clarity to legal traditions in general and specifically to the Seychellois legal tradition.

Chapter 2 Conceptualisations of Law

“[T]he origin of law is an unsolvable problem, a wound healed with fictions…”1

2. Introduction

Before attempting to analyse a legal system and its laws, it is important to establish what law is. The difficulty is that despite different concepts of law being advanced, there is no definitive consensus on what it is. Defining law is expressed by E. Adamson Hoebel as a quest for the Holy Grail,2 while the futility of the enterprise is acknowledged in Max Radin’s observation that “[t]hose of us who have learned humility have given over the attempt to define law.”3 This difficulty is due to the fact that too many “unbelievably different things have to be included in a comprehensive definition.”4 The obstacle in definition is compounded by a vocabulary that is not comprehensively utilised with the same meaning by jurisprudes.

Law in the West has generally stood for the “norms of specific institutions structured in specific ways in specific times and places”.5 As Seán Patrick Donlan has explained, the West sees law as “a subset of more general normativity, an institutional normative order”.6 In this way:

“law (legality) is distinguished from both less organised- but no less meaningful or valuable- instances of social normativity and the narrower, derivative form of state law (state legality)”. 7

For the purpose of this chapter and for the research of this thesis the following terms are adopted with the meaning ascribed to them as follows: the term law refers to a specific type of ordering or norm,8 the term official law refers to the law sanctioned by the legitimate authority of a state (including state law, religious law and laws of minorities within the state),9 the term norm indicates “standards of oughtness or appropriateness”, and “conventions with which the relevant community is familiar.”10 While official law is typically equated with state law, Seán Patrick Donlan suggests that both in Europe and beyond, law was conventionally understood as distinct from other normativities without merely equating to state law.11 Conceptually, it is a third category. Here, official law will be used to mean the positive law of the state.

Classical naturalists saw law as embodying reason,12 an “ordinance of reason for the common good, made by him who has the care of the community,”13 or “the set of principles of practical reasonableness in ordering human life and human community.”14 In contrast, positivists define law as rules established by political superiors;15 Marxists see it as a tool for the oppression of the proletariat by the capitalists16 while some legal realists saw law as “prophesies of what the courts will do in fact”17 or as “what officials do about disputes.”18 Hans Kelsen described law as normative but saw it as devoid of societal, moral, political or sociological values or considerations.19 Herbert Hart, however, saw law as a social construction, a system of social rules consisting of both primary and secondary rules.20 He explained primary rules as those imposing a duty, for example the rules of criminal law. He defined secondary rules as those setting up the procedures through which primary rules can be introduced, modified, or enforced: rules of adjudication (that is, those rules which empower officials to pass judgment), rules of change (those rules which regulate the process of change to the primary rules, for example the power to legislate in accordance with certain procedures) and rules of recognition (those rules that enable us to know that a rule is a valid rule, for example rules contained in statutes).21 He described any other system of rules made up exclusively of primary rules as pre-legal or primitive.22 Hence the rules of these communities do not form a legal system:

“In the first place, the rules by which the group lives will not form a system, but will simply be a set of separate standards, without any identifying or common mark…They will in this respect resemble our own rules of etiquette…[but] if doubt arises as what the rules are… there will be no procedure for settling this doubt…”23

Whilst Hart does not state that such societies are worse off than states with Western legal systems and laws, he does see them as being largely defective.24 He also would not label the rules of such societies as laws. In this respect African norms that existed prior to, or at the time of, European pre-colonialism would not have been deemed laws.

Others see law as an institutionalised normative order.25 However, both laws of the insititutions within the Westphalian model and other normative orders such as traditional mores are also recognised as being law. Laws can be defined as “normativities”, which concept would include state and non-state norms but also non-legal normative traditions.26 A possible consensus might be a definition that sees a “flexible working conception of law” which comprises “a species of institutionalized social practice that is oriented to ordering relations between subjects at one or more levels of relations and of ordering.”27

The purpose of this chapter is not to identify the true conceptualisation of law. It is clear from the very limited jurisprudential appraisal above that this is not resolvable. Instead, this chapter acknowledges the different conceptions of law and examines the difficulties associated with them, especially in defining the laws and legal system of any specific state. It enquires into the different manifestations of law and legal and quasi legal norms. It also addresses a further complexity in law, namely in the distinction or gap between the law-in-books and the law-in-action. The living law concept, as well as the related subject of legal pluralism is also examined as a useful construct for examining and appreciating unofficial law. Factors such as culture, politics, language and post-coloniality are also briefly surveyed for their influences on law. The purpose then would be to obtain a definition of law that would permit the analysis of the law of Seychelles in the subsequent chapters of the thesis.

2.1 The Complexity of Official Law

Law is most often viewed vertically as “a system of imperatives emanating from a hierarchically superior source”.28 As has been pointed out, in this positivist context, law is a state’s legal philosophy, that is, law exclusively emanating from the state. Hence, such law consists of legislation, regulations and principles expressly enacted, adopted, enforced or recognized by a government body, including administrative, executive, legislative, and judicial bodies. This may be defined as official law.

Masaji Chiba treats law as a three-tiered structure consisting of official law (that is, the legal system which is sanctioned by the legitimate authority of a country), unofficial law (a norm that is sanctioned by the consensual practice of some group either within or outside of a country), and legal postulates (that is value principles or system serving rules).29 He sees all three of these normativities interacting in any given state or community. This construct is progressively more recognised by legal scholars. However, it is increasingly difficult to clearly differentiate between official and non-official law, and between legal and non-legal normativities. The understanding of official law in some states, for example South Africa includes customary laws. Others include international or global norms into state law. This partly reflects the fact that people “seek justice in many rooms.”30

Nonetheless, within the strict confines of what is termed official law lies the further complexity of the law as appears in statute and law reports and the law that is applied by officials of the state.

2.1.1 Roscoe Pound: The Law-in-Books and the Law-in-Action

There is an obvious gap between the law-in-books, that is, statutes, regulations and law reports and law as practised and experienced in the legal arena generally. Roscoe Pound, the eminent American jurist of the first half of the twentieth century, was concerned with what he saw as a narrow view of law which essentially had to be debunked, that is, that the law that existed in law books was not the law as manifested in fact in the decisions of judges.

In his seminal paper in 1906 he stated:

“…if we look closely, distinctions between law in the books and law in action, between the rules that purport to govern the relations of man and man and those that in fact govern them, will appear, and it will be found that today also the distinction between legal theory and judicial administration is often a very real and a very deep one.”31

His main focus was to to express certain specific values in law not recognised in the law-in books. In his view, law had to be recognised as a dynamic system influenced by society and vice versa. He saw a focus on the law-in-action as a means to remedy conflict and reconcile social relationships. Pound’s treatise was written at a time when the United States was emerging from an agrarian, individualistic nation into an industrial and collective society.32 He saw jurisprudence as resistant to such change and still clothed in the “rags of the past century”.33 His call to make law vibrant, responsive and topical is summarised in his plea to lawyers not to become legal monks and not to allow “legal texts to acquire sanctity and go the way of all sacred texts”.34 His illustration of law’s fiction by using the Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn analogy of calling a pick axe a case knife when digging a hole so as to adhere to principle35 sums up the gap between the law-in-books and law-in-action.

Pound takes stock of the fact that although law must be stable, it cannot stand still.36 The gap between law and society must somehow be acknowledged and bridged. Law must proceed by taking into account the social facts on which it is based.37 A legal system must remain predictable but it must be flexible and responsive to change. In this context, he indicates that the spirit of the law rather than the letter of the law should be applied by judges. To coin a phrase of Walter Bagehot, the law-in-action must be permitted to break “the cake of custom.”38 Equally, as Marc Galanter has pointed out, law can be a fact to be taken into account rather than a normative framework that one is committed to uphold.39 This also ties in with Oliver Wendell Holmes’ claim that law is rooted in experience rather than in logic.40

In this respect, law must not be rigid or static but must respond to changes in society and human development. Pound summarises his vision of the law succinctly when he states

“There is no eternal law. But there is an eternal goal – the development of the powers of humanity to their highest point. We must strive to make the law of the time and place a means towards that goal in the time and place, and we do that by formulating the presuppositions of civilisation as we know it. Given such jural postulates, the legislator may alter old rules and make new ones to conform to them, the judges may interpret, that is, develop by analogy and apply, codes and traditional materials in the light of them, and jurists may organize and criticise the work of legislatures and courts thereby.”41

Pound rightly rejected Christopher Columbus Langdell’s declaration that “law is a science, and... all the available materials of that science are contained in printed books.”42 Pound’s concept of law is however limited as he sees law essentially about rules in constitutions, legislation or legal decisions. He does not see law in action as embracing all the social norms at play, nor does he see customary rules or social practices as capable of giving birth to legal norms without the intervention of the state.43

2.1.2 Legal Polycentricity

Pound’s “judge-oriented, common law-centric”44 perspective largely ignores other norms co-existing with state law. Although he accepts that there might be law without any political organisation,45 he does not expand on the possibility of the myriad of norms co-existing with state law. This shortcoming is partly addressed by legal polycentricity, a generic term used for non-statist legal systems in which customary law and privately produced law are subsets of state law.46 It may also refer to non state norms co-existing with state law. The term polycentric was introduced to the social sciences by Vincent Ostrom, Charles Tiebout, and Robert Warren to describe centres of decision making that are formally independent of each other but which enter into cooperative undertakings within a metropolitan area and function coherently.47

Using Iceland as an example, David Friedman demonstrates that some legal systems emerged spontaneously, as an extension of customary rules and at the realisation of societal self-organisation.48 Legal polycentricity is a well-established concept in Scandinavian legal science in which law is seen as being engendered in many different centres.49

Equally legal history also shows us that polycentrism was the norm in medieval Europe. As Donlan points out, after the fall of the Roman Empire “multiple contemporaneous normative and legal regimes coexist[ed] and overlapp[ed] in the same geographical space and at the same time.”50 In many other parts of the world, similar complex systems antedate the colonial or modern state, for example the coexistence of religious and non-religious conceptions in Indonesia.51

In more modern terms, Randy Barnett calls polycentric law nonmonopolistic law52 in contrast to monopolistic law where there is only one legal planner - the state. He predicts the growth of “private alternatives to governmental enforcement agencies” especially where these can be shown to be more “efficacious to provide law-making and adjudicative services.”53

Tom Bell asserts that unlike the common perception of legal positivists that the only alternative to stateless law is anarchy and chaos,54 polycentric law permeates society and functions in “churches, clubs, trades, and countless other settings where people associate freely and regularly.”55 We might in today’s world add global trading networks and the internet as other emergent orders with their own rules. Conversely, one might argue against pan-global law as essentially monopolistic and equivalent to super- statism. In the context of the European Union (EU) for example, the homogenisation of its laws will perhaps also develop into pan-European law which may not take advantage of individual national resources and knowledge although at present the preparatory stages of EU laws does involve studies of law, practices and experiences in Member States which are then built on.

Critics of the polycentric understanding of law argue that it fails to explain the enforcement of rules and the necessity in larger, more complex societies for a juridical authority system which therefore presupposes the existence of a state.56 Itai Sened has argued that spontaneous orders cannot enforce compliance with rules as they do not have the mechanisms to do so or they do not acknowledge the underlying state law that generally governs their function.57 He argues, for example, that property rights cannot exist without central government enforcement.58 Polycentric law, it is therefore contended, builds on pre-existing state structures for compliance.59 Hence, Geoffrey Hodgson concludes that “[l]aw relies to a large degree on custom, but law also depends on the existence of the state.”60

However, polycentricity is a concept that typically focusses on state legal pluralism. The issue of law is so entangled with the state that it continues to divert attention from wider categories of state law or other normativities outside those associated with the state. Finding a way to express normativities outside of the state is however a difficult enterprise as will be explored later in this chapter.

2.1.3 Rodolfo Sacco and Legal Formants

In his inspirational papers of 1991, Rodolfo Sacco61 borrowed the phrase formants from phonetics to explain the complex forces at play in determining the laws of a particular state at a given time. Sacco identified legal formants, that is, factors present in determining how cases are resolved, such as statutory rules, judicial decisions but also a judge’s background and bias.62 In an attempt to understand the deeper structure that characterises legal systems he

argued that “living law contains many different elements”.63 In this respect he explained that:

“The jurist concerned with the law within a single country examines all of these elements and then eliminates the complications that arise from their multiplicity to arrive at one rule.”64

However, there is neither one rule in any given legal system nor an identical comparable rule in another legal system as there is a certain element of incommensurability of rules given the fact that legal formants are equally incomparable, inconsistent and generally not uniform. Comparative law in general shows up how relative law in fact is. Neither statutes in civilist countries nor case law in common law countries are the whole of the law; these would be merely “legal flowers without stem or root, irrelevant to the actual law in force.”65

Sacco recognises that legal formants may not even be rooted in legal considerations alone; “[t]hey may be propositions about philosophy, politics, ideology or religion.”66 In this sense they are declaratory and hortatory and can be contrasted with operational rules which are simply imperatives.67 In describing some of these legal formants, Sacco reveals a wide range of sources for the content of law. In an exercise comparable to peeling back the skins of an onion, he finds that the influences behind statute and case law include scholarly doctrinal writings, sacralised rules,68 legal fictions,69 invisible or implicit rules,70 borrowings from other legal systems71 and innovations.72

Generally however, Sacco also focusses on official law. There is some acknowledgment of non-official law but this is limited to his recognition that implicit rules are those that play a role in what he calls the law of primitive societies.73

2.2 The Significance of Unofficial Law

Marc Hertogh has defined unofficial law or non-state law as “a body of norms produced and enforced by non-state actors.”74 Although this type of law may be seen as a heresy or not law at all,75 it has nevertheless to be acknowledged as a body of norms that is extant and increasingly impinging on the legislature’s presumed monopoly or at least in diminishing its exclusive role in the generation of social norms. Progressively, jurisprudes recognise the importance of unofficial law. Both MacCormick76 and Twining77 accept that an acknowledgment of unofficial law is essential for a genuinely global perspective of law. Indeed, this unofficial law may better embody justice, the rule of law, democracy and even human rights than modern Western state law. A balanced world view is essential. However, a jaundiced or romantic view of unofficial law, one that extolls the virtues of primitive laws may be counterproductive if not dangerous.78 The value of unofficial law is contextual, that is, important to people in a given time and place.

In Western democracies, non-state law permeates some fields of commercial law, international law, environmental law, tax laws and cyber law. Regulation, self-regulation or soft law have become major areas of expansion and debate, as have discussions on native or indigenous law. In the context of Africa on the other hand, the concept of ubuntu,79 although perhaps a universal value, illustrates one aspect of custom that may have preceded and have equal value to the great democratic precepts of Western legal tradition such as the rule of law and the exercise of human rights and fundamental freedoms, especially equality; not as an individual human right but in a social or communal interest sense.80

However, in order to appreciate the law of any given state, its setting must also be explored; the how and where of law dictates that the researcher looks beyond official laws to understand the impact of non-state laws and the living law.81 In other words, the context of

state law is important but equally important are the co-exising norms.

2.2.1 Eugen Ehrlich and the Living Law

Eugen Ehrlich wrote about what he called the living law (lebendes Recht) of the people of Bukowina, a community in a remote area of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (now Romania) in 1936.82 Populated by ethnic groups of, inter alia, Jews, Gypsies, Germans, Hungarians, Romanians, Russians and Slovaks, this melting pot of culture and norms influenced his realisation that the law of legal doctrine was far removed from the norms that were in actual practice. He used this experience to explain that quite separate from state law, other social orderings akin to law take place. He challenged the centralism of official law arguing that:

“The centre of gravity of legal development therefore from time immemorial has not lain in the activity of the state, but in society itself, and must be sought there at the present time.”83

Law preceded the state and enquiry into its definition and development has to extend beyond purely state centred law norms. In this context, he stated:

“[I]t is not an essential element of the concept of law that it be created by the state, nor that it constitute the basis for the decisions of the courts or other tribunals, nor that it be the basis of a legal compulsion consequent upon such a decision.” 84

He saw law not merely as a legislative, juristic or judicial concept but as a sociological phenomenon. Finding the law, then, takes a broader perspective than that contained in doctrinal expositions. It extends to local norms and shared practices even within familial associations.

Ehrlich’s contribution to the pluralist debate lies in his insistence that law is about social ordering, about rules of law emerging from the internal practices of human associations;85 and that from these associations and norms of social control, law emerges.86 This is a rejection of the monopoly of state-centred law, as Ehrlich’s theory sees living law as mainly developing independently from the state. However, Ehrlich’s elevation of orderings outside state law as law has produced much criticism.87 It is viewed as equating custom with law and confusing social behaviour with legal values.88

Nevertheless, Ehrlich’s living law remains significant, at least in the reinterpretation of his concept in the context of globalisation89 and also in the transcendence of national law.90 Specifically, Ehrlich’s conception is utilised by Günther Teubner in his autopoietic theory of law91 in which he sees law as the self-reproduction of specialized and organised networks of an economic, cultural, academic and technological nature.92 In Teubner’s view it is the decentred law-making process occurring in multiple sectors of civil society and not the global economic transactions or multinational organizations that create a global legal order.93 Essentially, Ehrlich’s contribution to conceptualising law is seeing it distinctively as a sociological way of understanding law’s identity.94

2.2.2 The Varieties of Legal or Normative Pluralism

William Twining defines legal pluralism as “a state of affairs in which two or more legal orders co-exist in the same time-space context”.95 Pioneers of legal pluralism, such as Ehrlich, did much to begin the debate between the co-existence of the law of the people and the law of the state. Such legal pluralism states that more than one legal order or mechanism can exist within one social space.96 But legal scholars also disagree on the boundary between normative orders that can and cannot be called law.97

Jacques Vanderlinden, like other legal pluralists in the 1970s at first saw legal pluralism as a plurality of norms administered by the state; then as just unitary systems “which “recognise” special rules for specific persons and/or purposes.”98 He affirmed that different devices applying to similar situations amount to “a plurality of legal mechanisms, not to legal pluralism”.99 While Vanderlinden perceived non state laws and state laws as only different méchanismes juridiques100 operating in identical situations,101 Galanter’s emphasis was on the processes of law or dispute processing. He shifted the definition of pluralism to an understanding of a plurality beyond norms administered by the state, that is, one that acknowledged “the multiplicity of norms of varying levels”.102

In his seminal writing of 1986, John Griffiths also challenged the ideology of legal centralism. He acknowledged that the co-existence of state law and non-state law is usual, “the omnipresent, normal situation in human society.”103 He concluded that whether one finds it possible to differentiate between different forms of law or not, law is present in every “semi-autonomous social field”,104 and “since every society contains many such fields, legal pluralism is a universal feature of social organization.”105 Sally Falk Moore acknowledged the operation of many of these social fields in any given society as semi-autonomous. She does not use the term law for these social fields, but sees them as units of social control.

Mariano Croce has observed that official law can appear as one social practice while other orderings could also be termed legal when they renegotiate social reality. Such orderings are engaged in a perennial struggle, competing “to affect both the special venue in which they enter when they need to solve disputes…” In this context, “legal pluralism can be regarded as a permanent condition of social reality”.106

In contrast, Brian Tamanaha distinguished between state law and other forms of normative social ordering, reserving the term law only for state law norms, including those instances where through recognition by the state, non-state law norms become incorporated into state law.107 Hence while the state may well claim to be the sole lawmaker, “legal pluralism highlights the multitude of partially autonomous and self-regulating social fields also producing legal rules.”108

Ralf Michaels warns against a linear genealogical view of pluralism109 in which one sees a progression of pluralism from its classical legal construct in the 1970’s, to the 1980’s new legal pluralism concept and today’s global legal pluralism. The term pluralism may only have existed since the 1970’s but the fact is that pluralism, as he points out, existed in medieval Europe and in the ius commune long before the colonial engagement of Western and non-Western norms.110 Martha-Marie Kleinhans and Roderick MacDonald have also pointed out that the legal pluralistic insight dates from at least Montesquieu.111

However, acknowledging legal pluralism across different times and spaces is only one step towards understanding law. Pluralist critics of modern monism often create strawmen, distorting the beliefs of contemporary jurists. Catherine Valcke has warned against caricaturing monism and has urged legal pluralists to recognise that despite their assumptions, state law theorists acknowledge relations between state law and other forms of normativity.112 She illustrates such acknowledgment by English and US state courts in family dispute cases involving Sharia law where the courts reach decisions dictated by such laws but through means that are “commonplace under the municipal law.”113

2.2.2.1 Classical Legal Pluralism

In the opinion of many, both within law and without, law is monist: exclusive, systematic, distinct and unique.114 This is explicit vertically either in the Austinian sense from the top down or the Kelsenian model of basic norm to grundnorm. Early legal pluralists refer to this as “the classical view of law”,115 though the latter only really dates from the nineteenth century. In contrast, classical legal pluralism recognises the co-existence of legal orders. Classical legal pluralism largely focussed on the colonial setting, identifying imposed colonial laws and customary laws or norms of the colonised community. However, as Michaels points out, such legal pluralism was confined in two ways: first, geographically it only concerned the interplay of Western and non-Western laws in colonial and postcolonial settings and secondly, conceptually, it treated indigenous non-state law or norms as inferior to the official law superimposed by the colonising power.116 This traditional view of pluralism is limiting not only in appreciating the true extent of pluralism within the colonised state but also in identifying the same competing orders in the colonising state.

2.2.2.2 New Legal Pluralism

Sally Engle Merry distinguishes classical legal pluralism from new legal pluralism.117 Relying on research carried out in the non-colonised states of Europe and/or industrial nations such as the United States of America she finds that

“Legal pluralism has expanded from a concept that refers to the relations between colonized and colonizer to relations between dominant groups and subordinate groups, such as religious, ethnic, or cultural minorities, immigrant groups, and unofficial forms of ordering located in social networks or institutions.”118

Hence, she finds legal pluralism in all societies. She does not see these different forms of law or orderings as competing but rather as participating in the same social field. One has to embrace Griffiths’ rejection of legal centralism119 to fully appreciate these non-state orderings beyond colonial settings.120 New legal pluralism thus sees legal pluralism as a universal concept.

Griffiths’ work, referred to above, depicts pluralism in all societies even those without a colonial past. He articulates the distinction between strong legal pluralism and weak legal pluralism. The former includes both state laws and non-state laws or norms; the latter focuses on the complexity of state laws or laws and norms officially validated by the state. In Griffiths’ view the latter is only a façade. State legal pluralism is of more importance. In contrast, Gordon Woodman recognises both weak (state) legal pluralism and strong legal pluralism as meaningful forms of legal pluralism.121

2.2.2.3 Global Legal Pluralism

To the extent that it reifies those very persons in communities creating the norms, both classical and new legal pluralism have been criticised by critical legal pluralists as pitting state law against other normative orders and more importantly as ignoring the relevance of the individual and the impact of laws or orders on him/her.122 In other words, the focus of legal pluralists should be on the narrative account of the legal subjects and not on the legal orders themselves.

If new legal pluralism reminds us of the complexity of law within the borders of the modern state, global legal pluralism recognises the interaction and engagement between different jurisdictional authorities within and outside the state. Boaventura de Sousa Santos describes this interface between

“the state and the interstate system as complex social fields in which state and non- state, local and global social relations interact, merge and conflict in dynamic and even volatile combinations.”123

Hence, plurality extends beyond local borders, beyond national time-space.124 He argues therefore, that whilst the pluralist debate was previously on “local infrastate legal orders co-existing within the same national time-space”, the present debate is focussed on “suprastate legal orders coexisting in the world system with both state and infrastate legal orders”.125 In this area, Roger Cotterell argues that the concept of law applied “should be judged by its fitness for the specific purpose for which it was created.”126 He concludes that it may be wise to be flexible about the social context when applying transnational doctrines and acknowledging the differing levels of institutionalisation of such concepts across different arenas.127

Paul Schiff Berman emphasises the complexity of this legal pluralism on a different level –

that brought about by nation-states sharing legal authority with regional or international courts and other tribunals or regulatory authorities.128 As he points out, the Project on International Courts and Tribunals129 identified about one hundred and twenty-five international institutions issuing decisions that have some effect on state institutions.130

Equally, the movement and displacement of peoples and communities across national borders has resulted in bonds of ethnicity dictating norms across those communities and displacing national law to some extent. Other ties across national borders include those of religion, commerce and cyber technology which are observed over and above and sometimes simultaneously with state laws.

In this context, comparative law and the study of mixed legal systems is linked to that of legal pluralism with the focus on the interaction between different state laws. More generally, it is important to note, especially in the context of Seychelles that mixed legal systems are often a manifestation of state or weak legal pluralism.

2.2.2.4 Critical Legal Pluralism

In an influential article written in 1997, Martha-Marie Kleinhans and Roderick Macdonald deconstructed legal pluralism, arguing that law is not an external force to be exerted and whose rules are faithfully obeyed by legal subjects.131 They observed that contrary to the traditional view that law and orders are social facts, critical legal pluralism “presumes that knowledge is a process of creating and maintaining myths about realities.”132 Hence, legal subjects create law and generate their own legal subjectivity. They are active not passive actors in the legal field. As Macdonald went on to say, law lives in people. It is the legal actors’ “purposes which law serves and their behaviour through which law is revealed.”133 As Macdonald states, legal pluralism is the:

“recognition of the inherent heterogeneity, flux and dissonance in the normative lives of human agents, the multiple trajectories of internormativity, and the fundamentally interactional nature of law itself- […] a view of the place of human beings in constituting their social and legal reality.”134

In this new perspective, legal pluralism becomes an interaction, a dialogue between the multiple differences, norms and modes of law and a marriage of laws and orders of human relationships.135 Critical legal pluralism has however come under attack for suggesting that legal subjects make or adhere to particular laws to suit their individual needs. Catherine Valcke has pointed out that law essentially governs individual interaction and transcends any one individual. Hence “legal pluralism cannot be recast as individual legality.”136 Insofar as critical legal pluralism assumes that legal subjects choose their own individual law this reduces the concept of law to anarchy.

Donlan has argued that distinctions should be made between normative and legal orders. In his view, although neither are superior to the other, by terming non-Western normativities as law, one commits a “conceptual colonisation”, assimilating such normativities to a “hegemonic meaning linked to Western ideas and institutions and drains each of their significance.137

In general, early theories of legal pluralism such as classical legal pluralism focus on state law as being dominant even where pluralism is acknowledged. Similarly, new legal pluralism views the state as the ultimate decision maker. Both global legal pluralism and critical legal pluralism do not pit official law against non-official law but rather they analyse the relations between the two types of laws or norms. It is the appreciation of the latter concepts that is adopted in the research on Seychellois law. Further, in the context of this thesis, it must be noted that in the formulation of Seychellois law, it is immaterial whether the mechanisms to be described are termed legal or normative. The distinctions are certainly important theoretically but not in practice.

2.3 Additional Cultural, Political and Economic Influences

In addition to the complexities of official and unofficial law already described, there are other other influences at play such as culture, politics and economics. Both the legislation and case law of a nation reflect the values of groups of people within it. Equally, the philosophies and policies of a political party whilst in government will influence the laws of the country. These political factors are closely linked to economic factors as political parties depend on voters to remain in government and are swayed by issues affecting the economy such as unemployment, taxes etc. Laws enacted or enforced reflect these influences at play. Equally, laws of economic and political unions or international associations have a transformative effect on national laws.

In this context the EU is an interesting entity to observe. On the basis of Union treaties, the legal orders of the member countries are constantly altered. The citizens of the EU are no longer mere citizens of member states but also Union citizens. Some sovereign rights of their nation states have been ceded to the EU. There is no denying the fact that the twenty-eight member states have autonomy on a large number of issues but it must be acknowledged that the fundamental ideas of the EU contained in Articles 2 (respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights) and 3 (the promotion of peace, its values and the well-being of its peoples) of the Treaty of the European Union138 have resulted in fundamental changes in the laws of individual member states. The fundamental freedoms have huge repercussions in terms, of inter alia, the freedom of movement of workers, goods and capital within the EU, as reflected in the laws enacted within the member states.

Equally, the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Court of Human Rights have far reaching consequences across the boundaries of member states. In this respect, inter alia, the right of ownership, freedom of opinion, the protection of the family, freedom of religion or faith as well as a number of fundamental procedural rights such as the right to due legal process have been enforced even when resisted by the courts of member states. Further, the Charter of Fundamental Rights is not only legally binding but also establishes the applicability of fundamental rights in EU law.